Catilinarian Conspiracy

63 BCE

Roman v. Roman

Marcus Tullius Cicero v. Lucius Sergius Catilina

In 65 BCE, Lucius Sergius Catilina (called Catiline in English) was unable to stand for consul because he was awaiting trail for extortion committed during his time as praetor in 67-66 BCE. It was said that Catiline organized a conspiracy to murder the newly elected consuls, L. Aurelius Cotta and L. Manlius Torquatus, on January 1, 65 BCE. However, Crassus seems to have smoothed over things.

In 63 BCE, Catiline ran once again for consul. Despite a strong proposal to cancel all debts — a proposal that widely appealed to the poor of Italy, the senators included — he was defeated by L. Licinius Murena and D. Junius Silanus. After he failed twice at being elected consul, Catiline turned to more underhanded methods in order to obtain the consulship. Many of his fellow conspirators included men who also had been thwarted in their efforts to ascend the political system. Catiline also rallied many of the poor, and Sulla’s veterans to his cause by promoting a policy of debt relief.

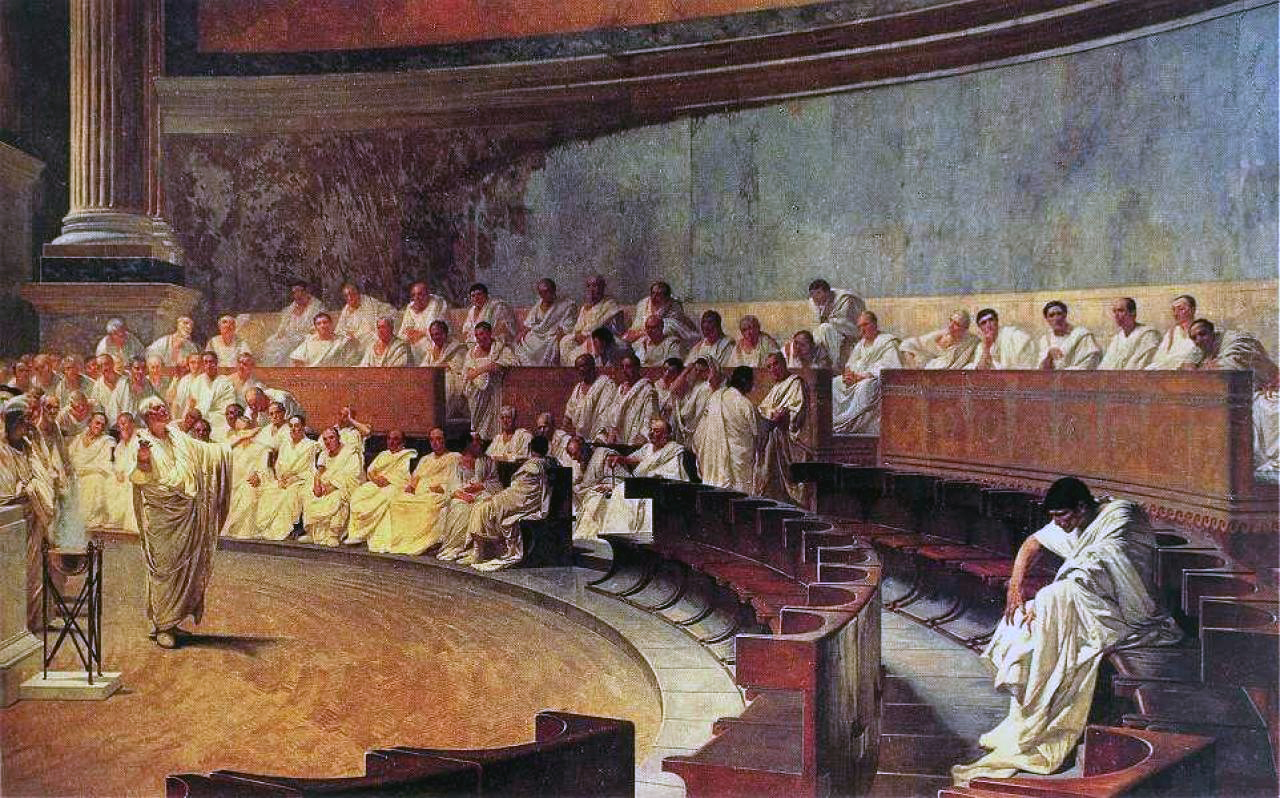

Gaius Manlius began to raise an army in Etruria (just north of Rome) while others began civil unrest around the countryside. Catiline, meanwhile, remained in Rome and continued to make plans there to assassinate a number of key senators on October 28 before the army moved to take the city. On October 21, the plot was discovered, and the conspirators adjusted their plans. They decided that Marcus Tullius Cicero, the consul at the time, should be assassinated on November 7, 63, that the city should be set on fire and slaves be called on to loot, to raise forces amongst the gladiators, herdsmen, and poor of Italy, and to march on Rome. Cicero, however, was warned of the plot and placed guards at the entrance to his home. On the next day, Cicero denounced Catiline in front of the Senate in the first of four Catilinarian Orations. Catiline vehemently responded to Cicero’s accusations and supposedly withdrew into exile at Massilia as Cicero had ordered. Instead, he joined Manlius in Etruria.

Cicero obtained actual proof of Catiline’s conspiracy from a delegation of Allobroges, a Gallic tribe, to whom the conspiracy had been revealed. Five of the leading conspirators penned letters, which the Allobroges were supposed to use as proof that there was a conspiracy afoot. These letters were intercepted, and Cicero used them as proof. The five conspirators were condemned to death without a trial. They were strangled in the Tullianum, the Roman jail. Within a month, Catiline's forces in the countryside had been subdued and Catiline had been killed.

This conspiracy marked a high point in the popularity of Cicero. After this event, Cicero was heralded as a hero, who had saved his country from a revolution. The Senate called him the Parens Patriae, "the parent of the fatherland." The event also demonstrated the amount of unrest among the upper class of Roman society.